Last November I wrote a piece called “A Hedonist’s Guide to Reading and Teaching Poetry.” There I suggest that to do either of those things well requires something of an artifactual approach to each poem. An artifactual approach is one which offers some resistance to the tendency to interact with the language in a poem as a signifying abstraction and instead to come at the poem as if it was a signifying object, like a painting or a statue. It is, admittedly, a more carnal approach to poetry than the bloodless academic route. You can test the argument as a whole here:

Pleasure and Poetry: A Hedonist's Guide to Reading and Teaching Poetry

In much of the morose educational discourse about preparing the young for whatever the adults intend to prepare them for (it varies by educational philosophy)—college, life, participation in the workforce, citizenship, sanctity, productivity, etc.—we rarely hear about pleasure or enjoyment. Nevertheless, one of the seldom acknowledged purposes of true e…

One of the questions that essay declines to address is: what are poems for?

We could go on and on about what poems are for, since every good object has some purpose it serves, but that is for another essay. The briefest introduction to the topic of what poems are for is that they impart shape and distinction to experience.

We’ll let that meagre fare stand for now and introduce the idea of this essay by noticing just one of the ways in which poems do what they do.

Poetry provides language for what leaves us speechless.

It has all sorts of techniques for this impossible sleight of hand: allusion, displacement, parallelism, compression, rhythm, rhyme, lineation, juxtaposition, understatement, misdirection, analogy, and on and on. It says what we can’t say sometimes through hyper-compression…”The apparition of these faces in the crowd: / Petals on a wet, black bough.” (Ezra Pound), and sometimes by extraordinary expansion, as in the Psalms.

But its unique ability to render in palpable form what otherwise takes our breath away has made poetry one of the perennial accompanists to war and its horrors.

In 1983 Czeslaw Milosz published a small book titled, The Witness of Poetry, which was drawn from his Charles Eliott Norton Lectures at Harvard University. The book reflects upon his experience of war in Eastern Europe during World War II. Milosz describes the role of literature, poetry in particular, in serving as a witness to the tragedy of war—a tragedy and trauma which tends to render its participants powerless to recount it. That is to say, renders them speechless.

He writes of those like him who come from a part of the world with recent “extraordinary and lethal events,” that, “we tend to view [poetry] as a witness and participant in one of mankind’s major transformations. I have titled this book The Witness of Poetry not because we witness it, but because it witnesses us.”

Poetry has stood witness throughout history to triumphs and tragedies alike as they unfold in different civilizations, landscapes, and individual lives. And for better or worse, war is one of poetry’s most prominent characters, its record as old as the oldest stories over told. If history records what happens in war by recounting and interpreting facts, literature also provides a part of the record, animating history with a host of human characters, their hopes and affects, and standing, just as memorials do, to mark in mourning or celebration the passage of war.

One form in which poetry serves as memorial is that of the elegy. An elegy is a poem which laments the deceased. In parallel to its impossible work of rendering in speech what makes us speechless, the elegy makes immortal in memory those who have died. Ancient warriors could battle fearlessly knowing that the bards would preserve their memory immortal in elegy. But those were in ancient wars.

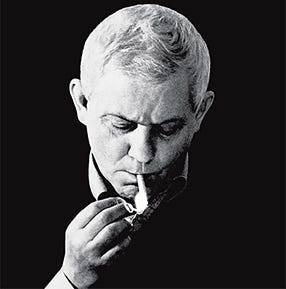

The Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert experienced warfare first hand in the streets of World War II Warsaw during extended operations as a member of the Polish Resistance and Home Army. He fought against both the Nazis and the Soviets. His poetry records the disintegration of a city, and significantly, the disintegration of culture that accompanies the loss of a city. Watching a library crumbling, and with it the paper on which his fellow poets inscribed their work, Herbert sees the death of language itself:

When we carried him off under fire, I believed his still warm body would be resurrected in the word. Now I see words dying, I know that there is no limit to decay. What will remain after us are fragments of words scattered on the black earth. Accent signs over nothingness and ash.

For Herbert watching a centuries-old civilization self-destruct, the ancient ambition of poets to be immortalized in their verse, bodies resurrected in the word, becomes as impossible as physical immortality. Not only are the words themselves as mortal and fragile as the bodies and civilizations from which they come, but even during their short life they prove ineffectual to achieve peace.

As Herbert witnessed the industrial-scale wars of the twentieth century, it occurred to him that even the word could not survive the exercise in erasure that surrounded him. Archaic heroes in the Greek epics thrust themselves forward in combat, sure that their memory would live forever in verse — sure, paradoxically, that they could achieve elusive immortality through death itself, so long as the death was glorious and worthy of commemoration in verse. But as Herbert watches the body-count rise and the civil structures fall, he envisions even a collapse of the theological Word — the animating principle and personality of Christian anthropology — into the frailty of simple earthly words which are prone to burning, forgetting, and all other forms of erasure.

Herbert suggests that to those who have experienced the totalizing wars of modernity, it is possible to believe that there will be no bards left to recite the epics, and no libraries still standing to hold the frail paper of history. To feel the concussion of high explosives detonating and to see their effect on the material world is to reverse T.S. Eliot’s prophecy from “The Hollow Men.” “This is the way the world ends / not with a bang but a whimper.”

Words, standing as they do for the human capacity to reason, are supposed to distinguish humanity from the rest of the natural world and demonstrate how like to God we are. But for Herbert the veteran, the word is made as ineffective as any individual human life faced with industrial destruction.

In his poem, “Elegy of Fortinbras,” Herbert describes the final scene of Hamlet from the young conqueror Fortinbras’ perspective.

Now that we’re alone we can talk prince man to man though you lie on the stairs and see no more than a dead ant nothing but black sun with broken rays... The rest is not silence but belongs to me you chose the easier part of an elegant thrust but what is heroic death compared with eternal watching... It is not for us to greet each other or bid farewell we live on archipelagos and that water these words what can they do what can they do prince

The poem is an elegy Fortinbras offers for the fallen Hamlet whose body he encounters as he ascends the throne of Denmark. Inscribed in the bloody scene of Hamlet’s death is the tale of inaction and frustration that marked Hamlet’s life. Herbert’s Fortinbras is impatient with Hamlet’s sensitivities. He describes the two princes (himself and Hamlet) as separate islands in an archipelago. “It is not for us to greet each other or bid farewell we live on archipelagos / and that water these words what can they do what can they do prince.” The archipelago represents a corporate body, like a family, village, or state where each individual takes its place as part of the whole. Yet in Herbert’s telling, each individual that comprises this whole is an island utterly removed from the others. The water lapping the shore, like speech, carries no meaning, or to follow Hebert’s question more closely, it does nothing.

Meaning is a peacetime luxury for the living.

Only tangentially related, but do you any recommendations for poems for boys (age 9-12) to memorize? (Can also be speeches, etc.)