Each month I share a few notes on the books I read during the previous month. The idea of the notes is to give anyone who might be interested enough of a glimpse into the book, at least what caught my eye, to decide if its worthy of your limited time.

One of the books I read in May was a volume of poetry sent to me by a gentleman named Garrett Soucy. I’ve come to learn that he is a Protestant minister, author, poet, and musician. His note came out of the blue, but I’m a sucker for poetry and thought I’d give it a read. I’m glad I did.

Between the Joint and Marrow Bones

by Garrett Soucy

This is a very ambitious book of poems by a minister from Maine. Not yet published, I had the opportunity to read the book in manuscript form and am grateful for the opportunity. I believe the book will be published this October by Fernwood Press.

The book is ambitious because its poems take one on a tour through the entire Bible. Familiar characters, events, and themes are displaced from their original contexts and rehearsed in new ones. The first poem in the collection, called “Moving Day,” wonders about a postlapsarian Eve. That must have been a traumatic move…out of the Garden of Eden. The last poem draws on the book of Revelation for its title: “7 Stars, 7 Horns, 7 Eyes.” Often, I had to squint hard to see the scriptural antecedent or correlative, and sometimes did not see it at all. But in my estimation, Soucy does not treat scripture as a grab bag of proven-profound objects to provide gravitas to the poetry (though one could do worse). Rather, his work in carefully displacing scriptural themes strikes me as an extended meditation undertaken as an act of piety.

This is not to say that the poetry forces pious readings or is over-heavy with religiosity. These are the dangers always threatening religious poets. I think Garrett threads the needle nicely. To be sure, these are religious poems. But they are not saccharine or moralizing. (I don’t mean to suggest there is anything necessarily saccharine or moralizing about religion, just that those distasteful elements often mar religious art.)

Not every poem suited my tastes. I don’t tend to like playing with font size or shape of the text on the page. And most of the poems scanned to me as though in free verse. I’m not a rigorist about this kind of thing but tend to think of meter and rhyme in a poem like clothing on a body. In a great poem, the less there is, the more alluring. But if there’s none at all then it’s simply naked and what’s the fun of that? Pardon the brazen analogy.

Speaking of brazen, Garret can craft a striking metaphor as in the poem “Brazen:” “The car needled through the mountains / Like a fingernail on corduroy.” But my favorite poem is a wintry reflection on the layers of technological mediation with which we insulate ourselves against the world and each other. The poem is called “Bunyan’s Oilman” and I'll quote a few lines from it in closing.

Perhaps it seems beautiful because it is Christmas and we know The Child will be crucified and so every sad thing glints a kind of beauty.... Perhaps it is because, in the car, everything is viewed through a screen. Perhaps Pascal was right and we are infants who cannot see the beauty Without mediation. We don't deserve museums. We are pretentious Children who need a soundtrack in order for moments to seem genuine.

Zen Haiku: Poems and Letters of Natsume Soseki

Translated and edited by Soiku Shigematsu

Natsume Soseki is a novelist. He wrote The Three Cornered World, The Gate, and Kokoro and many others. I came across a line of his poetry quoted somewhere and thought to myself, this might be something! His poetry is not widely available in English—I’m not sure how prominent his poetry is in his native Japanese or in the Chinese in which he sometimes wrote. On the strength of that one line happily encountered by chance I picked up his small volume of poems: Zen Haiku.

I regret to say that this book was a disappointment. There was nothing in these pages that achieved the level of the line I read elsewhere, a line which, sadly, I cannot now remember or locate. If there are any Soseki gurus out there who might point me toward a better collection of his poetry, I’d be grateful. As it is, there is nothing particularly offensive or pleasurable in this book. In my judgement, that’s a pretty damning verdict.

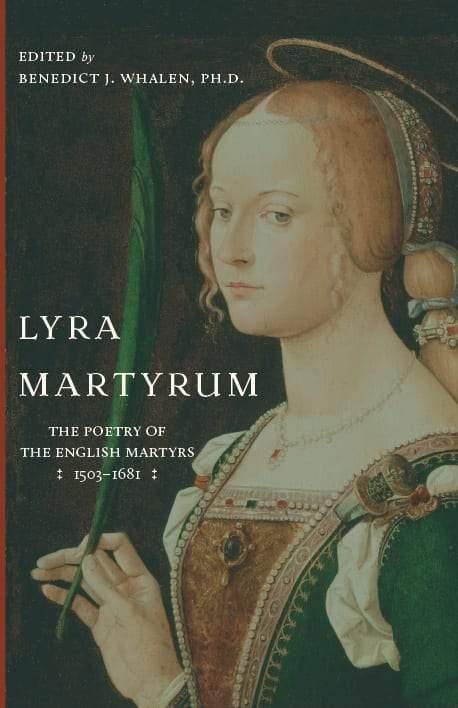

Lyra Martyrum: The Poetry of the English Martyrs 1503-1681

Edited by Benedict J. Whalen

Full disclosure: Benedict (the editor of this book) is my brother.

Lyra Martyrum was published in 2019 and is a collection of the poems written by Catholics who were put to death in England during the emergence of Anglicanism. Introducing each batch of poems is a short essay by my brother Benedict about the life, circumstances, and death of each poet. Most of these are not famous figures, or at least not famous for their poetry. Robert Southwell is a notable exception—well known for his “Burning Babe” which is included in this collection. Another headliner is Thomas More who is not best known for his poetry but was a prolific and accomplished poet nonetheless.

I told myself when I began writing this I would leave Henry VIII’s libido out of things. I really am doing my best folks.

The Many of these poems were written in prison in between rounds of torture and before being hung drawn and quartered. Here’s an excerpt from the book’s introduction that details the manner in which many of the poets (and other Catholics) were executed.

Hanging, drawing, and quartering was a particularly monstrous practice, whereby the condemned was hung by the neck, but, jst before losing consciousness, was cut loose and immediately placed upon a table and disemboweled as he lay dying. His organs were often tossed into a pot of boiling water, his heart lifted in front of the witnessing crowd, and his head cut off, to be placed on a spike above London Bridge or another prominent location. His body would then be cut into four parts, with each part sent to the four points of the compass and displayed in some other part of the city or land. Nor were these tortures confined to men; Catholic women were subjected to them and other, more particular violations. Often, groups of priests and Catholics would be executed together, one by one, with those who came later being forced to witness the butchering of their companions.

The brief, introductory essays to each poet are excellent and the poetry itself is pious and courageous. I imagine they all knew the stakes for which they were playing and enjoyed a particular clarity of mind as a result.

This book offers a tour of the history of Catholic persecution in England by the unusual route of poetry as primary text. There is a particular purity, and even privacy, to these primary texts as many of them were written by people in prison without hope of release. They offer a beautiful and sincere look into the heart of the faithful.

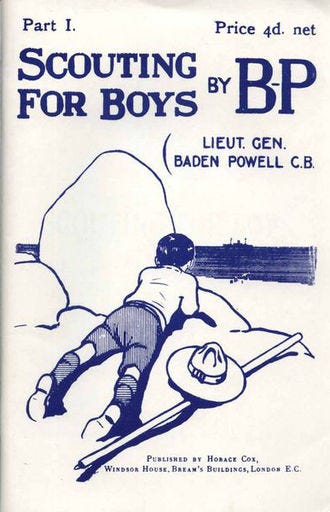

Scouting for Boys (1908 ed.)

By Robert Baden-Powell

Baden-Powell and Ernest Thompson Seton had a productive transatlantic relationship. Baden-Powell founded the boy scouts movement in England, and Ernest Thompson Seton in the United States. Each had been thinking and writing about a backwoods pedagogy for boys for many years before their efforts coalesced into a practical program. Scouting for Boys is Baden Powell’s definitive introduction to the subject and is comprised of six installments that were published separately over the course of the year 1908. Each one contains discussion of a main topic such as first aid, managing public panic, and tracking but also includes pedagogical insights into working with boys, practical suggestions for organizing troops, and ideas for particular crafts and games.

Implicit throughout the book is the idea that young boys can and should be useful and therefore ought to be capable. They can and should assist in emergencies and adults do them a disservice by coddling them and attempting to diminish their inherent desire to run toward the challenge. Conspicuously absent from its pages is any of the safetyism that plagues contemporary experience and drives many boys toward the lethargic despair of video games and other expressive forms of malaise. Baden-Powell’s opinions were shaped through expeditions and battle—shaped by contact with life’s rougher realities—realities that might serve as a tonic for our collective wishful thinking which proves so deleterious to the development of the young. Reality is a great teacher and this book is a kind of syllabus to the course reality proposes to teach.