Poetry and Translation

Translating poetry is one of the best ways to read it. I don’t mean reading poetry in translation which is a necessary, if evil, consequence of our ancestral indiscretion at Babel. No, I meant that undertaking to draft a translation oneself is one of the best ways to read a poem.

Translating a poem requires the kind of full engagement that every great poem merits but which we seldom give to poems in our native language. Full engagement includes spending enough time with the poem that it becomes deeply familiar—it moves beyond simple rational apprehension, driving roots into your memory and experience. It involves looking carefully at each word, it’s etymology and usage in the age of the poet. The translator must understand the structure of the poem in its original language, not just its lineation, but also the rhythm down to the letter. And a translator should have some understanding of the cultural, social, and political context from which the original emerged.

Language

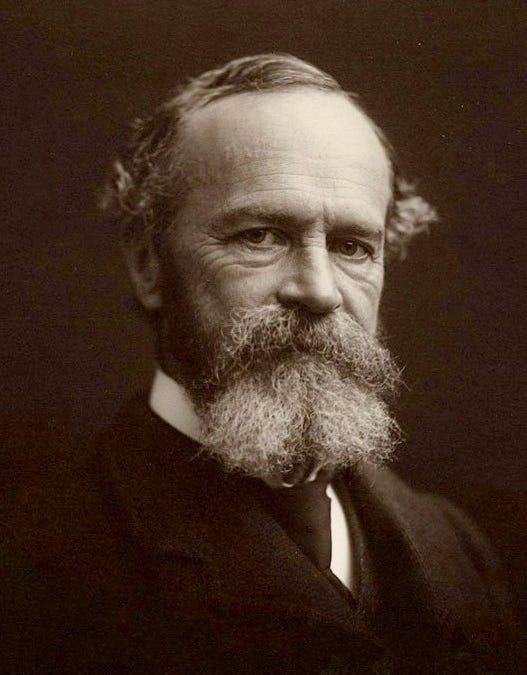

The language of the original is its first and most important context. It represents a barrier that creates a form of resistance the translator must overcome by spending time with the poem. Resistance is one of poetry’s signal features and is not a defect. James Longenbach’s book The Resistance of Poetry explores this dynamic more fully, but poetry resists immediate, easy, discursive handling in order to invite the reader to slow down and read the poem as poetry rather than prose. Poems sometimes communicate with a progression of rational statements (like a syllogism). Other times they communicate with gestures, insinuation, indirection, and absence. Absence in poetry often serves as an intentional omission and stimulates the mind toward something just out of our grasp. As William James writes in his 1890 book Principles of Psychology: “It is a gap that is intensely active. A sort of a wraith of the name is in it, beckoning us in a given direction.”

A translator studies the vocabulary of the original in order to determine the best words and phrases to capture the meaning in the poem’s new language. Fluency in both languages is helpful but not necessary as long as one is prepared to spend the time understanding the grammatical role(s) and etymology of every word in the original. I’ve worked on several translation projects alone but have also completed others with a friend who has the original language fluently. I find that the conversation with the fluent party emerges as one of the most rewarding aspects of this kind of translation. I’ll suggest a word that on paper (i.e. in the dictionary and usage guides) is a perfect match. My partner will squint and begin shaking his head “no” almost immediately, but will also struggle to explain why it doesn’t work. Usually this produces a conversation that focuses on the word at hand while situating it as an inevitable and irrevocable part of the whole poem. Replace the word with a poor substitute in the translation and you don’t really have the same poem at all. Intellectually it might serve, but then, that’s not why we read or write poetry.

Structure and Rhythm

You have to make some hard decisions when it comes to the poem’s structure and rhythm. How closely to adhere to the original? If closely, by which measure? Sometimes to get the right word you’ll be stuck with the wrong rhythm. Then again, sometimes the right number of syllables gets you the wrong number of beats (or feet as they are called in verse). Do all the main gestures and ideas appearing in line three of the original need to survive in line three of the translation or is it alright to tidy up the concept in line four? Or the original might subsist gracefully in dactylic hexameter but when you attempt to recreate the dactyls in English you end up with a sing-song palaver that insults the original.

Then there is poetry’s famous structural element: rhyme. Translation or otherwise, the question of whether to rhyme a poem or not is one of the most difficult. These things change all the time, but rhyme is either very cool, or not cool at all. This, however, is an eternal truth: if you put the thing in meter and rhyme you’re signalling to the English literary world that you are a hopeless linguistic Luddite and will be considered uncool. In the case of a translation, do it if you must, but proceed with caution and realize up front that you’ll lose some friends over the whole ordeal.

Aside from relative degrees of coolness, there are some real issues with carrying rhyme over in a translation. If working something into English from a romance language, you’ll likely find that the grammatical structures of the words often depend on changes to the end of the word. These grammatical changes produce rhymes (both internal and line-ending) that permeate the poem effortlessly and sustain a gentle, easy-going texture. You’re an honest translator and want to capture all that rhyme in English, so you go to work and next thing you know you’ve substituted the original’s ballet slippers for wooden clogs that thump mercilessly through every line.

Historical and Political Context

The translator’s understanding of the poem’s context plays a role behind the scenes, but it is a crucial role. Reverse engineering a poet’s psychological state when he wrote a particular poem is a mug’s game in which, nevertheless, a translator must dabble. But, knowing that the poem is a made thing, an artifact that stands outside the poet, translators ought to try and comprehend just where the poem stands in relation to its life and times. Poems do not always communicate at face value and a context-less translation might accidentally convey the opposite of the original’s meaning.

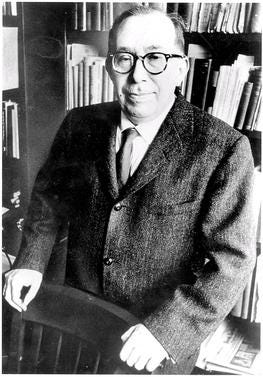

Up until the 1930s, all human beings read literary works exclusively for their surface meanings. Then Leo Strauss emerged, like Prometheus carrying esoteric fire from heaven, and taught humanity that sometimes authors hide things beneath the surface and between the lines. This stunning revelation ran through political philosophy seminars like wildfire and created a secular priesthood of readers versed in that subtle hermeneutics we now know by the mellifluous neologism: Straussianism.

We’re all grateful and wonder what reading was like before Strauss’s ministrations?

But seriously, which word to choose among several likely alternatives often hinges on the translator’s understanding of the big picture. This is where translation and original composition differ to some degree. While a poet without any learning but his own experience might achieve wonders inspired by the muses, a translator usually has to have something of the scholar about him and be disciplined in the traces. A great translator must be a great reader first and foremost—someone with a broad outlook and sympathetic intelligence. This is one of the many reasons translation is such an effective tool in education.

Taken all together, the translator’s task is very much like any student’s.

But there is an important distinction. The student often studies under the external compulsion of a teacher who strives to march his pupils through an understanding of each poem in a systematic way similar to the outline above. This is not an article about pedagogy, but if the teacher (and the poem) have earned the attention and affection of the student, then this works great. If not, then not. The translator, unlike many students, brings his own motivation to the work of understanding a poem, a motivation that is deepened by the practical attractiveness of solving a problem. Teachers might note the role translation can play in motivating students to engage with and integrate great literature.

The final element necessary for a good translation of a poem is perhaps the hardest of all. It is the spark of the poetic that allows the translation to stand on its own as a poem. It seems to me that this spark is unearned—yes, the ground-game has to be perfect: blocking and tackling each line just so, but in the end, a perfectly executed translation might not become luminous like the original. It appears to me that this is up to the muses who trade almost indiscriminately in talent and hard work alongside dumb luck and happy accident.