Restoring Raw Experience

Building the soil of raw experience necessary for learning to take root

Primary Texts and Objects

In classical education we often insist on the value of primary texts—texts written by the authors and historical actors themselves rather than those partially digested and repackaged by a scholar or company in the form of a commentary or textbook. Many of us agree, of course, that there is a balance here that depends on the right proportion achieved between the age of the student, the subject matter at hand, and the nature of the artifacts or texts relating to the subject. For example, a younger student might learn about the American Civil War through a combination of age-appropriate text books, period songs from the Civil War, pictures, maps, and perhaps even a field trip to a battlefield or space that resembles one. In this list of pedagogical tools, the songs, the battlefield itself, and possible the pictures and maps are examples of primary objects. Older students might study some combination of these objects while adding some of the texts written by politicians, soldiers, slaves, and other witnesses and participants.

This is straightforward enough and a preference for primary texts and objects enjoys widespread support among a variety of teachers. But there is another primary vs. secondary distinction that many approaches to education fail to acknowledge. The ultimate primary source for any student—for any person—is that provided by their own senses. We call this experience.

Experience builds the soul’s soil

Education is like gardening in that the teacher is engaged in the activity of planting and cultivating seeds. The student does the learning and no one can force him or do it for him. The teacher, for his part, tries to set the conditions for the garden to thrive. Following this analogy, we can see that many educational approaches assume that the little garden plot that represents each student is naturally full of good fertile soil and just needs the right seeds as subjects planted and sensibly tended. But what if the soil is not in fact healthy, nutrient dense and with good exposure to the sun? What if, despite an excellent curriculum and sound pedagogy, the student does not have a hospitable environment for the seeds of learning to grow? Is it possible to improve the soil? How can we help an individual soul to become more fruitful and susceptible to the growth of learning?

I believe we can improve the soil and the means by which to do so is experience. Experience and inherent ability are the chief components of any student’s susceptibility to learning (think soil quality). And since their inherent abilities are between God and their parents, we’re left to work with experience.

An individual’s experience constitutes their primary learning and growth. Objects of study in school, whether primary in the sense described above or not, are secondary in relation to experience. They depend for their purchase in the soul upon the primary experiences. The experience of love, or its absence, in a family will make Shakespeare’s Lear one kind of thing or another. A physical acquaintance with the aching pain of frostbite in one’s fingers turns the story of the Sebaste martyrs, or Robert Frost’s poem “Fire and Ice,” or the Battle of Leningrad, or the measurement of temperatures, or the biology of polar bears into something entirely different than if the student has never felt “the brutish ache of snow.” Sunrises, long journeys, hard manual labor, loneliness, downpours…we need them all even to approach the starting point of the people we study.

Proliferating examples threatens to undermine the point (a bit like the Bill of Rights) since, in fact, every single experience in life, including those had in school and of study, contribute to the soil of a soul and its ability to grow beautiful ideas, true thoughts, and noble ideals. The question we ought to ask is whether the way we live our lives and raise our children (and run our schools) constitutes experiential enrichment, or erosion? Are we living in such a way that the seeds of education will find fertile soil in our souls?

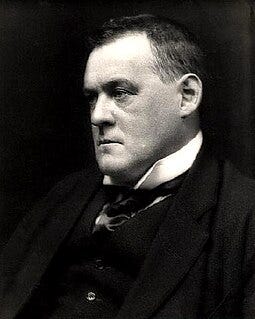

Hilaire Belloc’s short essay “Reality,” urges the salutary affects of its title upon all of us, however advanced our studies. He notes that education without experience is vulnerable to factual distortion and error, and perhaps worse, induces the student to certain flaws of character.

The truth is that secondary impressions, impressions gathered from books and from maps, are valuable as adjuncts to primary impressions (that is, impressions gathered through the channel of our senses), or, what is almost always as good and sometimes better, the interpreting voice of a living man….Well, I say, these secondary impressions are valuable as adjuncts to primary impressions. But when they stand absolute and have hardly any reference to primary impressions, then they may deceive. When they stand not only absolute but clothed with authority, and when they pretend to convince us even against our own experience, they are positively undoing the work which education was meant to do….Too much reading of battles has ever unfitted men for war; too much talk of the sea is a poison in these great town populations of ours which know nothing of the sea. Who that knows anything of the sea will claim certitude in connexion with it?”

I’d like to propose to you that we labor in an age requiring restoration in agriculture and education alike. Our vast mono-cropped fields are no longer fertile on their own. The implementation of the tools of mass cultivation have rendered them dependent on those tools alone for their productivity. So too our lives which lack rich variety of experience on account of the tools of mass culture insulating us against nature and its affects. For food, we go to the store rather than butcher a hog or harvest a crop. For warmth, we push a button rather than split the wood and stoke the fire. For mountain views we have our screensavers or, for the adventurous, a long drive and short hike to a “viewing area.” It’s tempting, but I’ll try not to carry on like a crank.

We need a restoration agriculture to make our fields fertile again. And we need a restoration of raw experience in order to provide worthy soil in which to grow the seeds of civilization. For parents and teachers—yes, that’s a fancy curriculum you have…would be a shame if it fell on barren soil. We need to do what we can to restore a minimally curated and mediated experience of nature and reality for our children—un-machined as my friends

and have said.Restoration experience will look a little different in the family and in the school.

I’ll write again soon with a roundup of simple ideas to start the work of restoration.

This is a beautiful analogy Patrick. It wasn't until I moved into the mountains that I actually became interested in soil health and grew the nerve to do something about it. We have a small food forest in the back yard, although it's fairly new and not yet producing anything.

The analogy also holds with my family. It took me a while to realize what actually mattered as I homeschooled my son. But as you said, it's not the pedagogy or the perfect curriculum. It's the relationship I have with him. That's what makes him learn. Him seeing me excited to build our plane, and excited to get beat at yet another chess match, or do another math problem. That's where the real fruit lies.

This is all so true. I teaching grade 2 to a demographic that has experience starvation. I’ve started prioritizing experience by bringing them outdoors more often, which has made a big difference. When we had snow outside, we went out in it. Some of them were surprised that the snowflakes were melting in their hands! Another asked if she could take her snowballs home. The experience was sorely needed. I wish we could do more, but it’s hard with a class of 28 kids. Homeschooling allows for so much more of that!