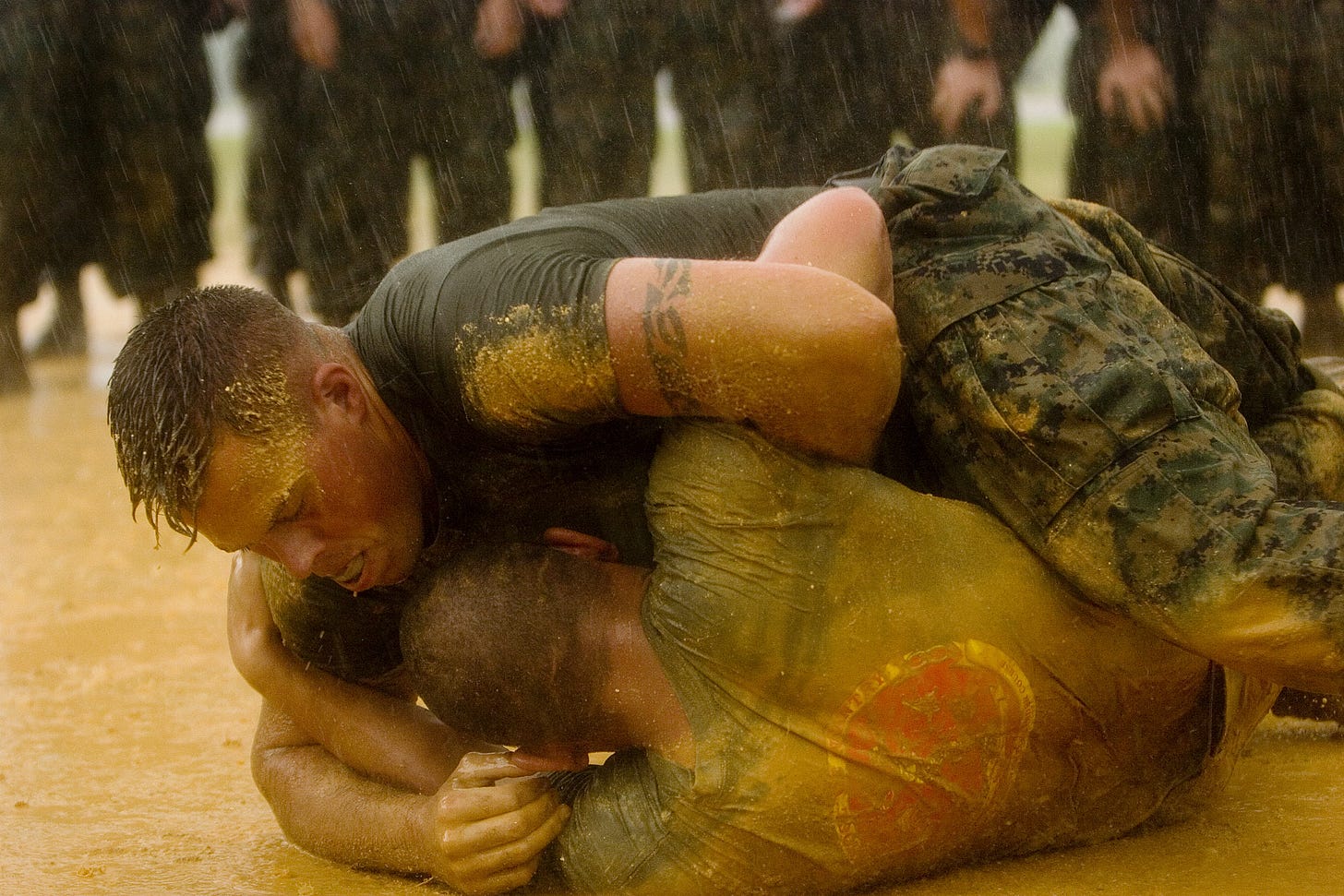

The Marine Corps developed a form of combatives in 2001 called the Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP). It is intentionally basic—a form of mixed martial arts designed to place a premium on hand to hand combat fundamentals and the mindset that goes along with them. It’s not fancy or elaborate in part because the Corps needs to teach a basic level of proficiency to every 18 year old that can make it through boot camp. The common denominator is the average Marine who is not a cage fighter, ninja, or hobbyist with time to spare honing his Jiu Jitsu.

A motto of the program is: One Mind. Any Weapon. The idea is obvious and compelling. Train Marines to be lethal per se. This is not the same as training them to manipulate a particular tool. That process comes later in their formation as Marines and is a form of specialization. But the Corps is very clear in its process that such specialization is only appropriate after they have been shaped into Marines.

I wish we had the same clarity in our efforts at educating children. How often do we mistake a particular tool as the object of education rather than the person?

The Corps begins teaching MCMAP in boot camp because hand to hand combat is not only an important part of the martial curriculum—it is part of the entire Marine paideia, a process of cultural instruction aimed at shaping who you are rather than simply what you know how to do or what tools you are adept at manipulating. Training one’s mindset is the chief object of MCMAP (just as the liberal arts seek to do in regular education). Marines should be ready for violence at any time, opportunistic and aggressive in a fight, and a generalist not limited to a specific weapon system but prepared to use anything at hand as a weapon of opportunity.

The Marine Corps knows, as many of us in education apparently do not, that they cannot prepare their students for every particular circumstance. Therefore, the use of particular tools is secondary to preparing students for what is primary and essential. Marines are made for martial strife. They are not made for drones, or bombs, or guns, or even knives. They might become specialists in any of those things, but only after they become Marines. They know from hard experience that no plan survives first contact; that this engagement may or may not be like the last; that technology changes every couple of years and keeping up with it is not within the purview of general education.

If you follow my analogy, what we used to call liberal education is just like the Corps’ boot camp. Its object is forming the human being for life rather than forming him around a particular tool. In my judgement, the liberal (meaning “free”) in “liberal education” is best understood not as an historical relic of a classed society of the leisured rich and the laboring poor, but as identifying the part of education which shapes one for life. It asserts that there is a part of every human which is free from the constraints of the particular tools by which he makes his living. That part is rational, free, and eternal and might decide to use any number of tools in its course of existence. Computers, for example. Computers are tools.

It is common today to hear folks call for schools to teach “computer literacy” as if it were an educational fundamental. Let me be ham-fisted for a moment. Computers are tools. They have no place as an educational fundamental. Furthermore, they are so prolific, and the mode of interaction they demand so totalizing, that they threaten a monopoly on attention itself. Like invasive species, this totalizing tendency can quickly choke out other objects of attention. This observation should not be controversial. Almost everyone has personally experienced the fundamental changes in how attention is apportioned in public places or in families that allow screen use in the home.

Screens and computers require a special place in education. And that place is very far away.

When I founded a boys boarding school several years ago, we maintained a strict no-screen policy on campus. As you can imagine, some prospective parents were concerned that this would place their sons at a disadvantage in the “workforce.” I should note that we were always clear about our disinterest in the “workforce.” We had other educational ends in mind and proved a good match for those families that were comfortable suspending career decisions until after their sons’ adolescence. But when it came up, generally I would ask two questions:

Isn’t your son already better on a computer than you are? (Usually they admitted that this was the case, an admission which helped reduce the specter of unemployable helplessness which looms so large for advocates of “computer literacy.”)

Active vs. passive voice: do you want him to use it, or him to be used by it? (I would argue that the computer as a tool is so pervasive today that our effort at achieving a short period of stand-off in high school was designed to give the boys a chance to conceive of the computer as a tool for them to use rather than the other way around.)

I don’t want to make light of the very real difficulties faced by people whose livelihoods are tenuous or threatened by AI, or offshoring, or mechanical automation, or whatever other disruptions advances in technology are causing. But it’s a good reminder that education worthy of the name does not depend on a particular technology.

It’s likely that tech will continue to evolve. Much of it plans its own obsolescence anyway. But how sad or cynical for us to fashion an education for the young which shares obsolescence as its terminal point rather than conceiving of it as contributing to a life of dignified freedom?

I propose we take a cue from the Marines on this one. Boot camp is about transmitting a culture, a mindset, and a core set of fundamental skills adaptable to any number of circumstances and changing conditions. Understanding that we are seeking to education children, not Marines, we should aspire to no less in education.

I remember learning MCMAP at the Naval Academy. It's funny how those moments still pop up when I training Jiu-Jitsu. When I first started, I kept thinking about how it would change if we had knives or other weapons.

"It asserts that there is a part of every human which is free from the constraints of the particular tools by which he makes his living. That part is rational, free, and eternal and might decide to use any number of tools in its course of existence." This is spot on. I've been trying to articulate the same point, but much less eloquently than you did. Thank you for the analogy here.

>It is common today to hear folks call for schools to teach “computer literacy” as if it were an educational fundamental.

My two cents:

Most of the folks who really got into computers, or video games, or any of the related technologies ended up doing so from their own initiative and cultivated intuition. The only fundamental that really needs working on is typing, because if you are a slow typer, your opportunities are limited. And fixing that is as easy as being sat down and told to write something on a machine (an essay, a story, an opinion, etc.) People adapt to the interfaces they are given.

Anything beyond that requires a bit of instruction, and that's OK. The softwares we're given are getting complicated. So long as you're canny enough to spot a scam, you're better than most novice computer users out there.