I was horrified to read recently of the design and construction of Brasilia—the federal capital of Brazil. James C. Scott describes the project in his book, Seeing Like a State, a study in politics and culture which is one of those books so illuminating of experience that you wonder at yourself for not having articulated the thing so clearly on your own. Blessed are the authors and teachers who, like Scott, trade in common sense.

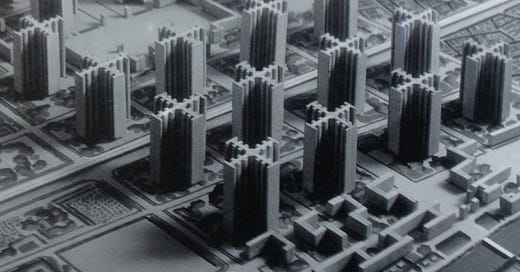

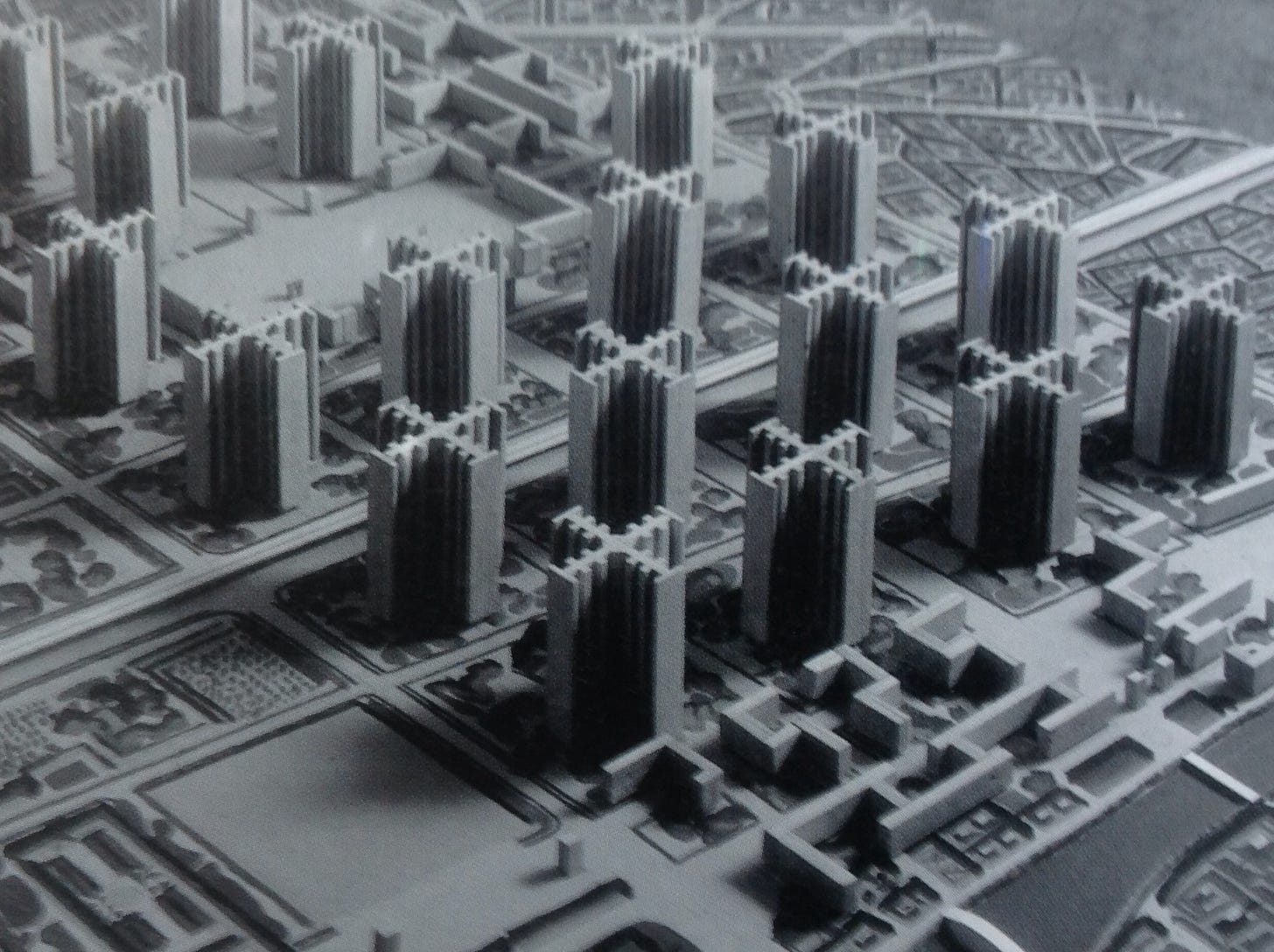

Architects Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa designed the city in a High Modernist idiom inspired by the famous, or infamous, Le Corbusier. The essential thing to know about Le Corbusier is that he wanted to replace Paris with this:

As with so many ideological political projects, the plans sought to impose a rational order on the messy human masses who were to inhabit Brasilia. This was a project to raze and flatten a piece of earth then to superimpose the architects’ vision on it with little to no reference to how people actually live. It organized space by purpose, segregating an administrative sector, a residential sector and a commercial sector and connecting these by massive traffic corridors. The complicated mixed-use urban environs that typically prove so hospitable to unscripted human interaction were planned out of existence.

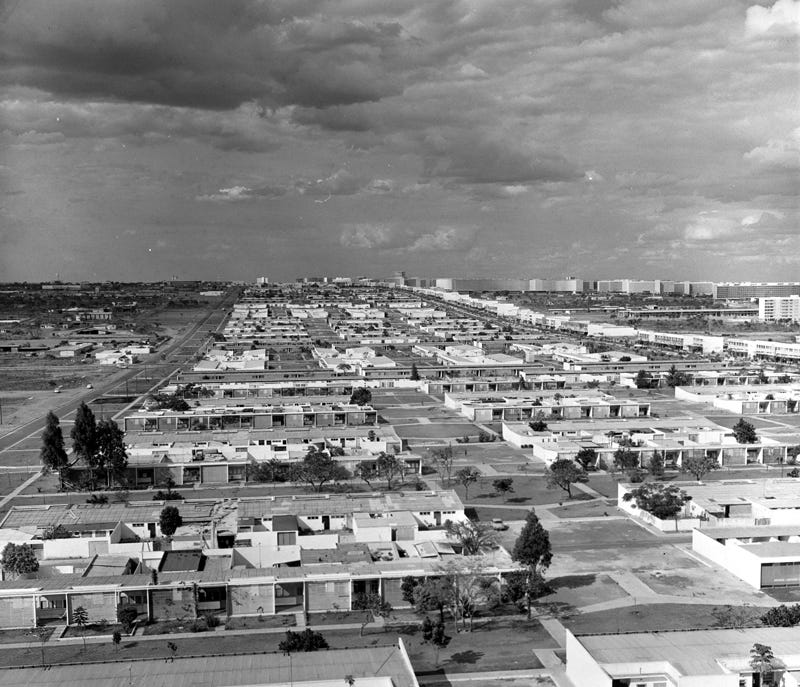

“The unplanned Brasilia—that is, the real, existing Brasilia—was quite different from the original version. Instead of a classless administrative city, it was a city marked by stark spatial segregation according to social class. The poor lived on the periphery and commuted long distances to the center, where much of the elite lived and worked.” (Scott, 130) The perfectly planned city was surrounded by Favelas where many people actually lived and suffered from rampant crime, lack of basic sanitation, and a general loss of 20 years in life expectancy.

The dystopian results of this utopian scheme might be apparent to you. They were not to the Brazilian president Juscelino Kubitschek. But the mistake is not difficult to make. We are are all capable of rational planning just as we are all capable of the hubris which so often turns our aspirations into mandates for others and our plans into prescriptions. It is rare indeed to find one who does not compulsively alter or interpret reality so as to fit a preconceived model which lives happily enough while inside one’s head, but withers in the warm light of reality. I imagine reality’s light as warm because of all the friction which inevitably attends upon it. Things are almost never just so.

Scott describes the organizing efforts of the state as chief exemplars of this tendency to wash reality thorough a rigged heuristic which, intentionally or not, delivers significance in a form legible only to bureaucrats. Simplifying complex information is, after all, the purpose of a heuristic. The information deliverable needs to be legible to the state which only knows what the state knows. The mistake is to think that the state and the individual people are coextensive and know the same things. They are not, and they do not. “There is no necessary correspondence between the tidy look of geometric order on one hand and systems that effectively meet daily needs on the other.” (Scott, 133)

One of Scott’s examples will appeal to any Marine who has spent time polishing boots or brass in advance of an inspection and wondering what in the hell this has to do with killing the bad guys. An army on parade is an army doing nothing and doing that nothing for the purpose of displaying itself in an orderly form to the brass. An army at war displays no such orderliness—and would be wise not to. The actual virtue of the army is functional. It is validated not by parade, but by victory in combat.

All of this made me think about education. Architecture, after all, is not the only arena in which utopian hubris has brutalized humanity in an effort to achieve rational ends. We know education is important and we should strive to do it well. But we are also familiar with the temptation to hubris, and know that institutional, top-down efforts to organize human affairs, rather than organic bottom-up efforts have a checkered record.

The order that facilitates actual human thriving is likely to be highly complex and might not fit neatly into our model regardless of whether that model consists of a particular institution, institutions, or curricula. I’ve been involved in founding institutions as well as in writing curricula and consider the story of Brasilia a welcome warning.

Strive we must, but always carefully, even reluctantly, when casting an educational vision or curriculum.

American state financed education does exactly what it is currently designed to do: it crushes the creativity and intelligence out of the young as they are propagandized and lied to by some of the least intelligent and least creative people in our society. It also does it's level best to destroy the masculine impulse whilst at the same time ignoring the subtle, insidious, vicious tendencies towards destruction that drive almost every girl who is at or near the top of the her little social structure. Public schools were designed around the way girls learn. Boys triumph over it in spite of the design and the purposeful rejection of who they are and how they learn.