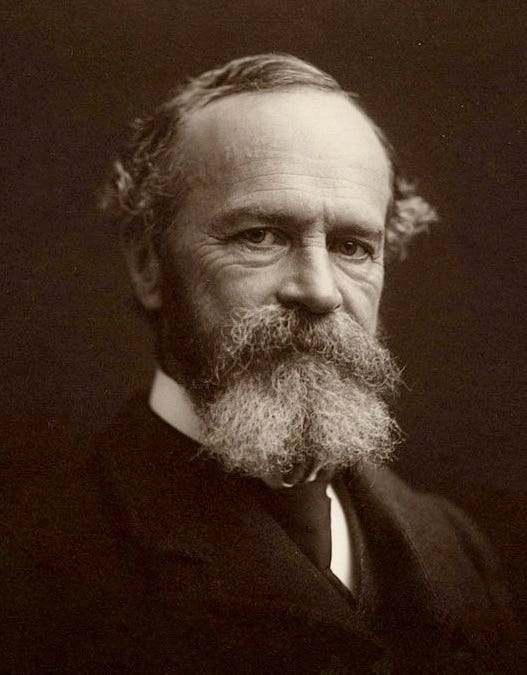

William James is not a poet in the conventional sense. But if part of the poet’s responsibility is to craft new words and new expressions through metaphor, then William James is surely due a pagoda somewhere on Parnassus. James is famous for his psychology and philosophy—not disciplines to which we turn for the soothing balm of inventive and lucid prose—but he brought a poet’s facility with language and metaphor to his work.

It might surprise you to know that James was the first to transfer the word “trauma” out of the strictly physical realm where it served as a synonym for wound. It was James who gave the word its now dominant sense of psychological injury when he described how one suffers from a “psychic trauma,” a wound or a thorn in the soul. The strength of the metaphor dominated the original use of the word and extended its meaning so that, for most of us, the first meaning of trauma is psychological rather than physical.

The study of etymology is a carnival of this kind of thing.

James’ contemporary Ralph Waldo Emerson described this process of forming language and extending our cognitive and communicative reach in an essay called “The Poet.”

Though the origin of most of our words is forgotten, each word was at first a stroke of genius, and obtained currency, because for the moment it symbolized the world to the first speaker and to the hearer. The etymologist finds the deadest word to have been once a brilliant picture. Language is fossil poetry. As the limestone of the continent consists of infinite masses of the shells of animalcules, so language is made up of images, or tropes, which now, in their secondary use, have long ceased to remind us of their poetic origin. But the poet names the thing because he sees it, or comes one step nearer to it than any other.1

“Language is fossil poetry.” For example, the word “window” derives from the Old Norse “vindr” (wind) and “auga” (eye). This might be one of the most prosaic words to us, but for some ancient Scandinavian, the very eye of the wind pressed against his house.

William James provides another example of this language formation in his now famous formulation of consciousness operating as a stream. His essay “The Stream of Consciousness” deploys the analogy of a stream of water to describe that human consciousness is in constant change, is continuous, and that even the same objects of experience do not result in the same consciousness of them.

We feel things differently accordingly as we are sleepy or awake, hungry or full, fresh or tired…and yet we never doubt that our feelings reveal the same world…. Within each personal consciousness, thought is sensibly continuous…. Consciousness, then, does not appear to itself chopped up in bits. Such words as “chain” or “train” do not describe it fitly as it presents itself in the first instance. It is nothing jointed; it flows. A “river” or a “stream” are the metaphors by which it is most naturally described. In talking of it hereafter, let us call it the stream of thought, of consciousness, or of subjective life.

James’ metaphor for consciousness is rightly famous. And I propose that it provides some reasonable hope and encouragement for us in a variety of circumstances, perhaps especially painful or regrettable ones. The objects of our experience might be poor or painful and unchanging: the same grind day in and day out—or the same flaws. But how we come to them and integrate them in our consciousness is perfectly, and almost inevitably, changeable.

To this changeability of consciousness I’d like to add one additional Jamesian proposal which I find encouraging. In a lecture on pragmatism, James argues that our decisions and actions turn possibilities into realities, thereby crafting being itself.

Our acts, our turning-places, where we seem to ourselves to make ourselves and grow, are the parts of the world to which we are closest, the parts of which our knowledge is the most intimate and complete. Why should we not take them at their face-value? Why may they not be the actual turning places and growing places which they seem to be, of the world—why not the workshop of being…?

We have the opportunity and the responsibility to make decisions and act, and thereby to labor with the dignity of a craftsman in the “workshop of being.”

Allow me a very simple illustration drawn from my own recent experience of these two Jamesian concepts: the stream of consciousness; and the workshop of being.

Standing before our house are several large oak trees. They run in a line fifteen feet or so from the road and although they are beautiful, the road makes them a somewhat inhospitable area for children to play. Other than collecting the trees’ acorns for our pigs, my children rarely spent any time in that part of the yard.

I recently cleared several trees from our wood lot which had fallen in storms this year. Rather than immediately splitting and stacking them in the round stacks I typically use, I simply stacked them whole as a log wall between two of the oaks in front of the house. I embedded an old wagon wheel to provide the wall some additional visual interest allowing the surface of the wall to rhyme through its curve with the curve of the logs which constitute it.

Almost before I had finished the work, two of my children were clambering all over the wall, balancing and pacing back and forth along it. In what was previously a “dead zone” in our yard it’s not uncommon now to see one of the kids pacing along the wall in a reverie or fully immersed in some imaginative world which the wall unlocked for them. Even the oak trees, which have not moved in a hundred years, have pulled themselves together as familiar objects of play.

As I say, I think James was right in describing consciousness as a stream which takes in its course the same objects differently, oak trees and a stretch of lawn for example. This simple wall became a turning place in which my children and I brought a part of the world a little closer, made it more intimate and complete. “Why may they not be the actual turning-places and growing-places which they seem to be, of the world—why not the workshop of being?”

“Language is fossil poetry.” So perfect. Great essay, Patrick.