Bare Recommendations: Reading February and March

Hilaire Belloc, Mark Shepard, Guy Kawasaki, Gil Bailey.

Every two months or so I write briefly to introduce the handful of books I’ve read in the last two months. These are hardly book reviews. Those are an art form all of their own. Instead these are the barest notes which assume many busy people are cultivating a rich intellectual life and might appreciate such notes introducing them to a few titles they might have been wondering about or about which they might have never heard.

Hilaire Belloc:

The Hills and the Sea

First and Last

Do you often find what you’re looking for when you set out to read? I don’t mean in the way a student searches a textbook for an answer, or the way a researcher scours documents for the facts. I mean, do you sit to read for leisure (leisure including not just recreation but the cultivation of the intellectual life) and find an electric current flowing from the page to you? Or a channel cut into the earth of your experience through which meaning and importance rush like water?

Sometimes I do and sometimes I don’t. This has almost as much to do with me as it does the particular book and author. I find that, like the land, we too are subject to seasons—seasons of the soul—and sometimes the water flows, sometimes it’s frozen. And then there are in between seasons. Like plants, few authors can thrive and bear their fruit in every season.

Of the books I read in the last few months, few offered the electric jolt of realization and connection. But two books of essays by Hilaire Belloc did.

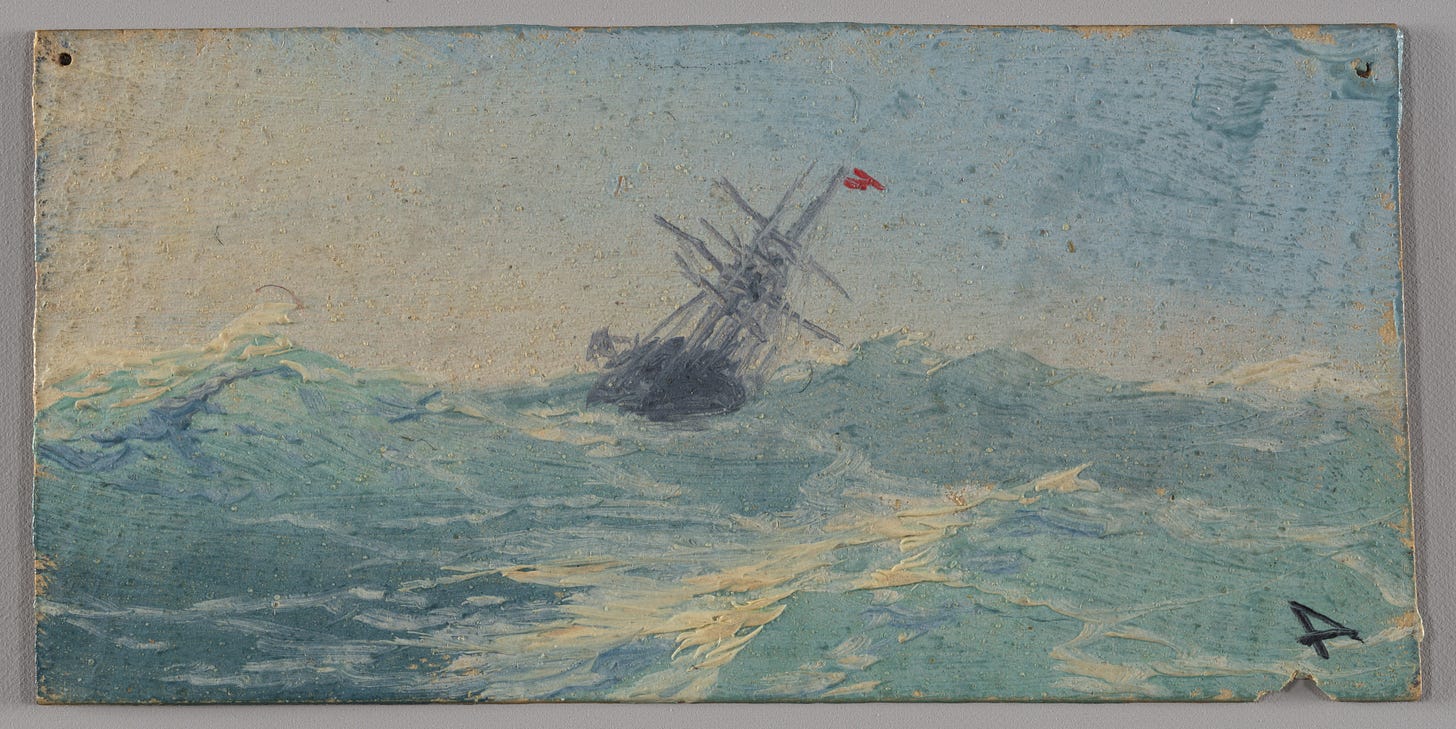

There is a three volume set of Belloc’s essays that has just been published by the Cenacle Press from Silverstream Priory in England. These are handsome, cloth-bound, hard-covers and the forwards for two of the three volumes are written by my father, David M. Whalen. In one of the short forwards my old man writes of the essays, “they display the sure tone of a natural teacher, of a master unfolding the manner of things. This master however remains ever a companionable guide.” So companionable in fact that most of the time I was reading I wished to be trekking alongside Belloc as he traversed the woods of France and mountains of Spain, or sailed the seas around England in a small boat, or even as he settled in for a simple meal and good red wine at little inns all over Europe. His essays tell all about these things and make you fall in love with them. Some of the essays are chronicles of his extensive travels, some polemics, some paeans to a dying Catholic culture in Europe that gave to Europe what remains of it that is picturesque and ancient.

Belloc the man comes through his essays as one firmly grounded in reality—an apologist for reality, in fact, as I noted in a previous essay about the increasingly tenuous relation between education and reality:

Belloc exemplifies a whole man. He laughs, cries, argues, and eats without neuroses, featuring instead, manly good cheer, a mischievous streak, and a formidable intellect. Perhaps best of all, he tells us his adventures in mountains, oceans, and inns in such a way as to exude encouragement for us too to cast out in adventure as whole human beings. Belloc was “No mouse of the scrolls.”1

Restoration Agriculture

By Mark Shepard

The contention Mark Shepard seeks to refute in this book is that industrial scale mono-cropping of staples (corn, soy, etc.) is the only way to feed the earth’s population. This is a contention I have myself heard many times, often by folks condescending to or criticizing our efforts to grow or raise our own family’s food. The comments go something like this: “That’s a cute enough pastime for you and yours, but don’t mistake it for real farming of the sort needed to feed the world.”

Not knowing any better, and not intending to feed the world myself, I have always acknowledged the point while reserving from that kind of conversation my private judgements as to my interlocutor’s own information, experience of “real farming” and various other forms of reality, as well as motive in at least implicitly encouraging my abject dependence on a massive, regularly pathogenic, and dubiously sustainable industrial food supply system. Nevertheless, I am not a real farmer and even less am I a real statistician of the sort to draw conclusions from abstract data sets about what staple crops need to be grown where in order to feed the world.

I’ll even admit a certain bull-headedness about the whole enterprise of “feeding the world.” Perhaps you will find this morally reprehensible, but I’ve never really taken that particular task on as my direct responsibility. Instead, I focus on feeding my family and assume that most others are locally focused in the same way I am. Subsidiarity and solidarity apply especially to the corporal works of mercy. In agriculture, as in defense, I fear that systematizing provision of these life essentials to others on a global scale creates a moral hazard through which risky or unsustainable behavior is implicitly encouraged. But anyway.

Mark Shepard is a real farmer, though his farm looks nothing like the dust-bowl-inducing mono-chrome mono-cultures that comprise what most of us think of as farming. His farm in Wisconsin looks much like what a natural landscape would look like if human intelligence and ingenuity partnered with nature to encourage its fruitful aspects and discourage its pathogenic ones in such a way as to induce it to be productive and harvestable without intensive chemical or mechanical intervention. He calls his particular take on agroforestry: Restoration Agriculture.

If any of this grabs your attention, I highly recommend the book. Mark’s prose is clear and approachable, his ideas are inspiring, and the data he assembles useful. In short, mono-cropping corn and soy is not the only way to grow staples. Mark argues that anywhere corn grows, chestnut can grow—chestnut providing a nutritionally dense annual crop as well as an overall contribution to a diverse ecosystem filled with other food producing plants and animals. Savannas, mixed ecosystems of trees, grasses, and shrubs, support more animal life than any other ecosystem. And while Mark acknowledges that mono-cropping genetically modified corn can produce an incredible number of calories per acre, he notes that man does not live on calories alone. In fact, he argues that our current staples are nutritionally deficient even when they technically provide enough calories. Just imagine a people stuffed to the gills with calories and all suffering from malnutrition. You can imagine can’t you?

Art of the Start

By Guy Kawasaki

A friend of mine who is a ninja, metaphorically and in reality, recommended I read Guy Kawasaki’s Art of the Start. You might know that I started a company called Iliad Athletics which seeks to reintroduce the body in education. If you regularly read Adam’s Curse you’ll have a general familiarity with our philosophy and probably understand how the company seeks to put it into practice starting with any kid, anywhere. We have a PE curriculum for functional fitness, train teachers of all stripes, and consult with schools about the proper role of the body in education. And while that’s what the business does, how it does largely depends on me doing a good job launching and leading it. All things being equal, I’d like to do a good job if I can. Hence the Art of the Start.

I won’t anatomize the book, but just offer the following observations and endorsements. Kawasaki is a marketing guy. Actually, he’s a marketing Guy. This is not a management book, it’s more focused on marketing. With that said, he offers practical advice about how to take an idea and turn it into a viable, profitable business. His experience and focus is chiefly in the tech world, but there was plenty here for me and my luddite tendencies. Probably the best thing about the book is Guy’s relentless common sense and down to earth advice. Identify milestones: 1) Working prototype 2) Initial capital 3) Field testable version 4) Paying customer 5) Cash-flow breakeven. (Bonus points if you can tell where in the mix Iliad Athletics is.) Bootstrap or find capital? Partnering, enduring, profitability? They all get concise chapters.

Oh, and asking the question right at the start…would the world be worse if your product did not exist? Yes, because without Iliad Athletics, formal education would lack an inspiring physical component resulting in poor health habits and loss of integrated experiential learning. (What do you think?)

Apocalypse of the Sovereign Self

By Gil Bailey

Bailey’s method of argument in this book struck me as somewhat unusual. He suggests that the person of Christ substantiates any humane and dignified understanding of human personhood. The book does not really proceed to argue this point but rather to suggest it through an accumulation of anecdotes and illustrations. Certainly, there are arguments. But much of the book’s 317 pages are comprised of lengthy quotes from philosophy, psychology, fiction, and theology that explore various aspects of human personhood and are collected to shed light from a particular angle.

One of the dominant themes in the book is the conception of Rene Girard’s of mimetic desire. Bailey follows Girard in describing mimetic desire as normal within the human condition. Why does it matter? Because humanity is susceptible to wanting what others want, the frame, environment, or social / sacred order within which a life unfolds can have a huge impact on what that individual wants in his life and therefore what kind of life he has. Bailey points out that the social order which existed in Christendom placed the person of Christ at the center of all good desire. This fact oriented generations of people, even not particularly devout people, toward desiring lives that exemplified Christian virtues. The social structures emerging from the majority of people sharing this fundamental orientation toward particular virtues are not inevitable.

Like the other blessings we have enjoyed by virtue of living in a culture under Christian influence, many today experience degrees of interiority and social solidarity without realizing how indebted to Christianity they are for these blessings, or that these blessings will not long survive the waning of the faith that made them possible. (3)

As he argues later in the book, the Christian position, for example, regarding the sanctity of human life from conception to natural death is no guarantee that our social structures will organize themselves accordingly. Indeed, it is already out of fashion in much of the world and the emergence of cyborg theory and its ilk in the academy portend more to come. This piece from a couple years ago describes the movement and how to combat it with…movement.

Survival Among the Cyborgs

This piece first appeared two summers ago shortly after my team of former Marines involved in Iliad Athletics wrapped up one of our summer camps for young men. We've spent the intervening years refining our approach as we developed a method and curriculum for physical education which we are planning to pilot with a number of partner schools in the comin…

If none of this feels like a big deal I’ll just observe that a brush with death at the hands of other willing humans re-writes very quickly your expectations of security and personal integrity. The whole “sanctity of human life” gig is a pretty good one to have…if you can keep it. Bailey’s book suggests that the only way to keep it involves an orientation around one particular person.

As always, appreciate these round-ups... and walk away with another book to add to my reading list.