Cruellest Month Books

T.S. Eliot called April the “cruellest month” in his famous poem “The Waste Land.” As if taking him up on his proposition, we now call April poetry month….

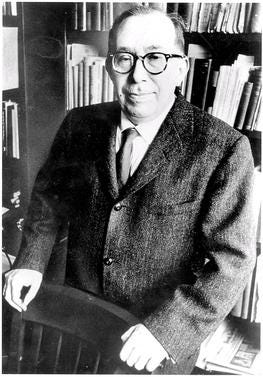

I wrote recently about translating poetry and I’ll lead this list with a beautiful book-length poem in translation by the great Czeslaw Milosz.

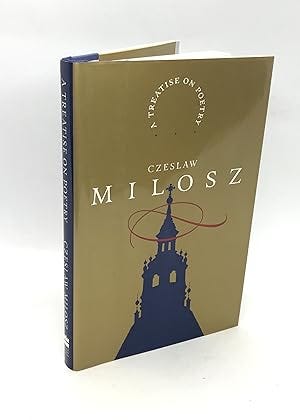

A Treatise on Poetry by Czeslaw Milosz

“One clear stanza can take more weight than a whole wagon of elaborate prose.”

Czeslaw Milosz was doomed to live in interesting times. A child during WWI and a young man in WWII, Milosz was a diplomat to the US for the Polish Communist government during the Cold War until he defected in 1951. Seeking asylum in France he eventually made his way back to the United States where in 1960 he began teaching at Berkeley. Observing the student protests of his day he described Berkeley students as the “pampered children of the bourgeoisie.”

A Treatise on Poetry is a book length poem, written in 1956 in Polish, but translated in 2001 into English by Milosz himself (assisted by Robert Hass). It has four cantos, extensive notes, and is the mature work of one of the most interesting, experienced, and capable poets of the 20th and 21st centuries. Like most of Milosz’s self-translated poetry, it works surprisingly well in English. You gain a sense of the poet’s voice that is consistent and recognizable. The tone is straightforward and elevated—like an old-timer telling a story that accidentally reveals the old-timer as a great poet. The topic is world-historical and metaphysical without being pretentious. Milosz called sophistication a great enemy of poetry. This poem would be sophisticated in the bad sense if it weren’t for Milosz’s broad and sympathetic sincerity in sorting through the detritus of civilization’s fall.

A few of the important themes that run throughout the poem:

-Poets are barometers of social disintegration: “a skein of common values came undone….a poet without a community rustles in the wind like dry grass in December.”

-Being as essence vs. being as becoming.

-What it is to be caught between two parts of oneself or two competing desires: on the one hand, the historical and political nuanced symbolized in the poem as architecturally intricate European cities. On the other, natural simplicity and beauty symbolized by sex, countryside, and animal life.

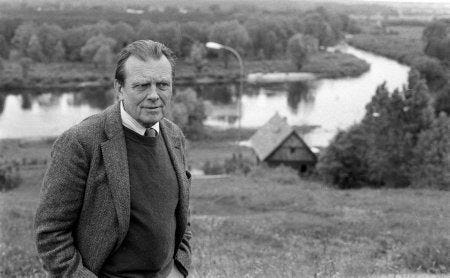

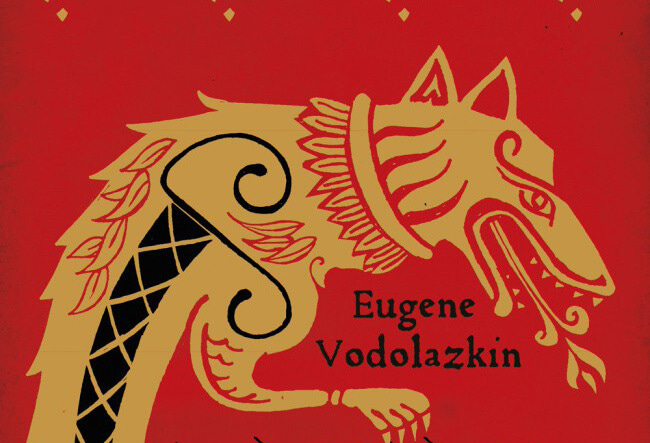

Are we allowed to read Russian books these days? Laurus is a recent (2012) novel by the Russian Eugene Vodolazkin. To my knowledge there is only one English translation which is by Lisa C. Hayden and was published in 2015.

Set in 15th century Russia, Laurus tells the story of a young man living a spiritually attentive life. Arseny is an orphan, an herbalist, a healer, a penitent, and a holy man. I will not summarize the story. Much that happens in the book might cause you to think it is borderline fantasy—miraculous cures, prophetic visions, suspension of physical laws (walking on water)—but I don’t think it is intended as fantasy. It simply offers at face value a story which assumes the truth of orthodox Christian cosmology. This makes it seem pretty foreign to us contemporary readers who, if we could suspend our chronological (progressive) chauvinism, might see a valuable perspective in the medieval mind. (A friend of mine mocked our contemporary view of history by caricaturing teachers pronouncing the medieval period as the “middle-evil” period.)

This is not a plot-driven book and the prose comes through the translation in funny and unexpected ways. Surprising informalities and colloquialisms pepper the text which is nevertheless a highly engaging read. Laurus offers reflections on healing, sin, and herbal medicine; on the intertwining and also conflicting trajectories of history and free will; on memory, knowledge and nostalgia. For the pilgrim and penitent it offers the following insight: faith is motion; knowledge is repose.

Laurus has a satisfying, earthy feel to it that is probably best summarized (like most things) by a line from a Tom Waits song. “Now I’m smoking cigarettes and I strive for purity.”

Boy Scouts Handbook 1910 by Ernest Thompson Seton and Baden Powell

You might have read that the Boy Scouts no longer exists. It has been replaced by an organization called Scouting America. If you read the 1910 Handbook and compare it to vintages from the last several decades you might come to the conclusion that the Boy Scouts stopped existing some time ago.

The vision laid out in the 1910 handbook, however, is very impressive.

Perhaps my favorite aspect of this book is how wise it is about human nature. It’s a primer on pedagogy that will benefit any teacher. In fact, the problem with the Boy Scouts rebranding as “Scouting America” is not that it affords girls the opportunity to learn fieldcraft. Of course girls should learn fieldcraft. The problem is the subordination of pedagogical common sense to political fashion—a willful attempt to erase or ignore the simple, natural differences in how boys and girls learn best.

Seton describes teaching boys with an analogy of fishing:

When you are trying to get boys to come under good influence I have likened you to a fisherman wishful to catch a fish….Use as bait the food that the fish likes. So with boys; if you try to preach to them what you consider elevating matter you won’t catch them. Any obvious “goody-goody” will scare away the more spirited among them, and those are the ones you want to get hold of.

….Discipline is not gained by punishing a child for a bad habit, but by substituting a better occupation, that will absorb his attention, and gradually lead him to forget and abandon the old one.

Sometimes schools that are trying especially hard to do a good job lose sight of this last point and make an idol of Prussian style disciplinary measures better suited to industrial acculturation than human flourishing.

This book can teach you how to dig an Indian Well (if you don’t have access to clean running water); tie knots, light fires, track game…conduct hostage negotiations with juvenile males…it’s all here folks.

School is Dead: Alternatives in Education by Everett Reimer

Everett Reimer was a friend and colleague of Ivan Illich at the Center for Intercultural Documentation (CIDOC) and this book derives from his decades of conversation with Illich about the role of schools in education. Reimer makes some good points, but honestly, you’d be better served by reading Illich’s Deschooling Society.

Reimer is a bit heavy-handed with his Marxist heuristic applied to every angle of the question even if we agree that school is a regressive tax on the poor and the church of a technological society. Illich is concise and constructive whereas Reimer takes longer to wade through the argument, laden as he is with the inflated jargon of academic Marxism.

With that said, I am grateful to have read the book because it alerted me to the existence of a pamphlet written by Benjamin Franklin around the year 1784. In the pamphlet Franklin told the story of some government officials in Virginia who thought to do the Indians of the Six Nations a good turn by subsidizing the college education of six of their young men. Franklin quotes the beautiful response:

We know that you highly esteem the kind of learning taught in those colleges, and that the maintenance of our young men, while with you, would be very expensive to you. We are convinced, therefore, that you mean to do us good by your proposal and we thank you heartily.

But you, who are wise, must know that different nations have different conceptions of things; and you will not therefore take it amiss, if our ideas of this kind of education happen not to be the same with yours. We have had some experience of it; several of our young people were formerly brought up at the colleges of the northern provinces; they were instructed in all your sciences; but, when they came back to us, they were bad runners, ignorant of every means of living in the woods, unable to bear either cold or hunger, knew neither how to build a cabin, take a deer, nor kill an enemy, spoke our language imperfectly, were therefore neither fit for hunters, warriors, nor counsellors; they were totally good for nothing.

We are however not the less obligated by your kind offer, though we decline accepting it, and to show our grateful sense of it, if the gentlemen of Virginia will send us a dozen of their sons, we will take care of their education, instruct them in all we know, and make men of them.

Yep. That hurts a little doesn’t it?

A World Without Email by Cal Newport.

Cal might be in the process of saving my life. Saving it from the crushing gravitational pull of work commitments (commitments I am responsible for making).

Cal Newport has written a series of books that generally fall into a genre we might call “productivity self-help.” It’s pretty much like Laurus but not for the spiritual life. (For those who mistook my sarcastic dig at Straussian self-seriousness in a previous post as an earnest compliment, I hasten to add that this is a joke.1)

If you’re like me and your inbox is trying to kill you, this book might help. Of course, you can’t simply ditch email and presume to work without it, but Cal anticipates this problem and offers a variety of helpful solutions. He describes the systems that programmers use to manage projects—tracking progress through a series of cards and columns. He suggests meeting protocols to prevent the rapid context switching that inevitably happens when one tries to work from one’s inbox. He reveals that the frenetic busy-work (he calls it the hyper-active hive mind) that many bosses demand from their employees produces less value in the end.

It is an eminently sane book about working in a world driven more than a little crazy by the very technological tools we developed to make work more sane.

Good luck.

From the Up until the 1930s, all human beings read literary works exclusively for their surface meanings. Then Leo Strauss emerged, like Prometheus carrying esoteric fire from heaven, and taught humanity that sometimes authors hide things beneath the surface and between the lines. This stunning revelation ran through political philosophy seminars like wildfire and created a secular priesthood of readers versed in that subtle hermeneutics we now know by the mellifluous neologism: Straussianism.

We’re all grateful and wonder what reading was like before Strauss’s ministrations?

…but seriously.

Poetry in translation is yet another work. Just compare the poetry of Li Bai李白 or, for that matter any Classical Chinese poet from any reign-date, as written, to its modern English translation, even to the best of them. Most of it is missing in the translation and much that is foreign has been added.